Full Description

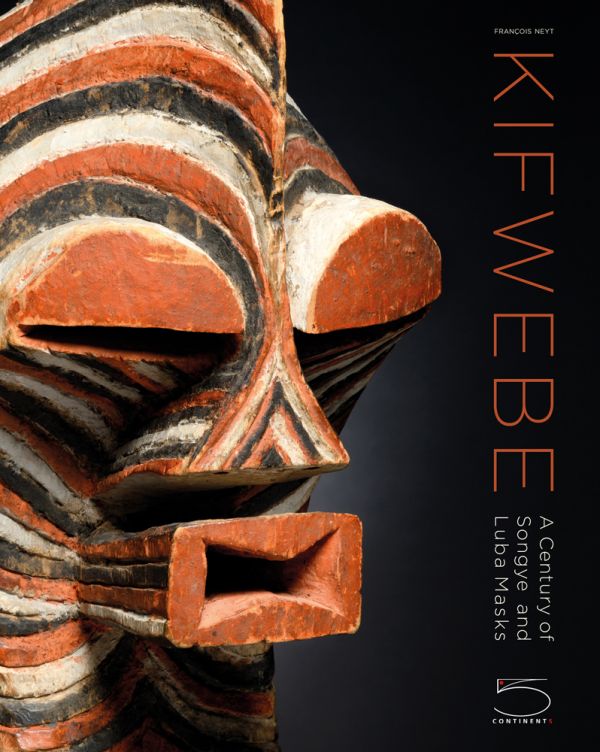

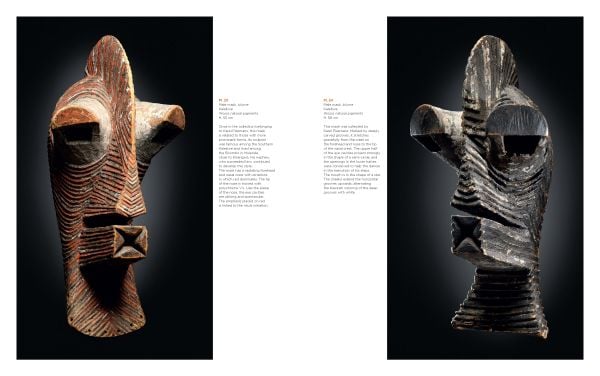

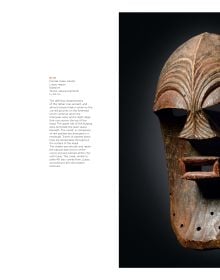

Kifwebe masks are ceremonial objects used by the Songye and Luba societies (Democratic Republic of Congo), where they are worn with costumes consisting of a long robe and a long beard made of plant fibres. As in other central African cultures, the same mask can be used in either magical and religious or festive ceremonies. In order to understand Kifwebe masks, it is essential to consider them within the cosmogony of the python rainbow, metalworking in the forge, and other plant and animal signs. Among the Songye, benevolent female masks reveal what is hidden and balance white and red energy associated with two subsequent initiations, the bukishi. Aggressive male masks were originally involved in social control and had a kind of policing role, carried out in accordance with the instructions of village elders. These two male and female forces acted in a balanced way to reinforce harmony within the village. Among the Luba, the masked figures are also benevolent and appear at the new moon, their role being to enhance fertility. Although the male and female masks fulfil functions that do not wholly overlap, they do have features in common: a frontal crest, round and excessively protruding eyes, flaring nostrils, a cube-shaped mouth and lips, stripes, and colours. Art historians and anthropologists have taken increasing interest in Kifwebe masks in recent years.

About the Author

François Neyt is professor emeritus at the Catholic University of Louvain and has also taught at the Official University of the Congo. As a Benedictine monk, he has been chairman of the Inter-monastery Alliance, covering over 450 communities throughout the world, and is also member emeritus of the Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences of Belgium. François Neyt has published several works on African art, including La Grande Statuaire hemba du Zaïre, 1977; Arts traditionnels et histoire au Zaïre, 1981; Luba. Aux sources du Zaïre, 1993; La Redoutable Statuaire songye d’Afrique centrale, 2009; Fleuve Congo, 2010; Fétiches et objets ancestraux, 2013; and Trésors de Côte d’Ivoire, 2014. He has also organized several exhibitions: at the Musée Dapper, in Paris, 1993; at the Etnografisch Museum, in Antwerp, 1994; and at São Paulo, in Brazil, 2000. The Congo River exhibition he organized at the Musée du Quai-Branly Jacques Chirac, Paris, in 2010 subsequently travelled to Shanghai, Seoul, Mexico, and Moscow (Pushkin Museum).

Allen F. Roberts is Distinguished Professor of World Arts and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. His studies of sub-Saharan African humanities include A Dance of Assassins: Performing Early Colonial Hegemony in the Congo (Indiana University Press, 2013) and, with his late wife Mary Nooter Roberts, Visions of Africa: Luba (5 Continents, 2007).

Kevin D. Dumouchelle earned a PhD in Art History and Archaeology from Columbia University. His doctoral research in Ghana examined architectural modernity in Asante. In 2016, he joined the National Museum of African Art. He was the lead curator for Visionary: Viewpoints on Africa’s Arts (2017). He has additionally served as coordinating curator for World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean (2018) and Good as Gold: Fashioning Senegalese Women (2018). His latest exhibition, Heroes: Principles of African Greatness, opens October 2, 2019. Previously, Dumouchelle served a decade at the Brooklyn Museum as the curator in charge of the arts of both Africa and the Pacific Islands. At Brooklyn, he conceived two award-winning re-installations of the African collection: African Innovations (2011) and Double Take: African Innovations (2014). He has written books and articles on a range of topics and curated exhibitions on both contemporary and historical African art, including Power Incarnate: Allan Stone’s Collection of Sculpture from the Congo (2011) at the Bruce Museum and the Brooklyn Museum presentations of Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui (2013) and Disguise: Masks and Global African Art (2016).

Woods Davy lives in Venice, California. For the past thirty years Davy has worked with stone in unaltered states, either from the sea or the earth, incorporating them into assemblages of precarious balance that appear to be in flux. He might be thought of as among the first “green” Postmodern artists. In fact, he comes from a long tradition of post-1960s artists, who either directly or just by their practical sensibility engage Eastern or Zen notions of oneness with nature, organic systems of change as engines of art composition, and non-disruptive respect for natural material in unaltered states. These works manage this, as they illuminate the poetry of nature. As Holly Meyers observed in the Los Angeles Times, there is “something thrilling about a work that appears to defy its own natural properties,” while at the same time one can appreciate the work’s “meditative reverence.” A recent Cantamar sculpture was acquired in 2018 by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, adding to the 1986 steel and stone sculpture in their permanent collection. His work is included in many other California museums and institutions, such as the Palm Springs Desert Museum, Orange County Museum of Art, San Diego Museum of Art, Grunwald Art Center-Armand Hammer Museum, Long Beach Museum of Art, Laguna Museum of Art, as well as numerous public and private collections throughout the world. He has completed large-scale sculpture works for the State of California, City of Beverly Hills, City of Los Angeles, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cedars-Sinai Hospital, University of Southern California, Baylor University, IBM, Neutrogena, ARCO, Prudential Real Estate, Metropolitan Life Insurance, Qatar Museum Authority, among many other public collections. Woods Davy is represented by the Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, CA; and has had one-person exhibitions in New York, Paris, Houston, San Francisco, Chicago, Washington, DC, as well as with numerous galleries throughout the US.

H. Kellim Brown holds an MA in African Art History from the University of South Florida. He completed two internships at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African Art in 1997, and as a result was offered and has maintained a research position at the Congo Basin Art History Research Center in Brussels, Belgium, since 1999. In 2008 he held a research position at Portugal’s National Museum of Ethnology focused on Angolan traditional art production. His published texts include “Ritual Art from Southern Congo (Brazzaville),” 2001; “Transatlantic Kongo: Echoes of the Cosmogram,” 2003; and “From Tidewater to Tampa: Yard Activation in the Kongo-Atlantic Tradition,” 2013. Brown’s ongoing fieldwork in the Democratic Republic of Congo produced: “Southern Kasai Hands: Notes from the Field on the History of the Bakwa Ndolo and Two Schools of Sculpture,” 2011; and “Crossing the Lega Ivory Spectrum: A Contemporary Ride Through ‘Heavy’ Things in Maniema,” included in White Gold: Black Hands Vol. 6 (Gemini Sun, 2013). His work among the Lega in 2011 led him to further investigate ethnicities of the northern Democratic Republic of Congo from 2012 to 2015, yielding a recently published essay in Congo Masks: Masterpieces From Central Africa (Yale University Press, 2018).